Once I asked my husband how I should refer to myself when people ask “What do you do?”

“How ‘bout an Advocate?”

“Naw, everyone is an advocate for something.”

“Activist?”

“Powerful, but maybe a little too powerful.”

“How about a Blogger?”

“Out of the question,” I said. I was deep in the throes of the “no one will ever read my stuff” anxiety that, I am told, most writers experience. Confidence was not on my side.

“How about, ‘Stephan’s wife’?” I asked. Always my true north, Stephan groaned. While he loves that I am his wife, he has always been my “never let anyone reduce you” proponent . Gently, he suggested I skip to my sweet spot, “You are an educator.”

I tried it on.

“I am an educator. I like that.”

I started teaching 25 years ago. I have taught in state of the art classrooms, cinderblock boxes and under banana trees. Of all the things I do, I believe learning is a literal miracle—making one bigger on the inside than the outside.

But learning should be what educators do best. My most life changing lesson came not from a classroom but from a bullet-riddled village. My most important teacher was a woman without a degree, pomp or prestige. She was genuinely one in a million.

Her name is Esperance.

She said, “You remind me I am still human,” unfolding the corners of her story in the light of glass-less church windows. Her name means “hope.” She lives in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the poorest country in the world, where a woman is subject to sexual violence every 60 seconds and rape is cheaper than bullets. She told me her story in three acts.

Act one: she flees her village and her family is displaced. Destination unknown.

Act two: she is the sole witness of her husband’s murder and she is brutally raped, beaten beyond recognition, and abandoned. For days.

Act three: sisters from a local church find and take care of her. Her own words,

“I didn’t die. They saved me.”

As the story ended we knelt together on the dusty concrete floor. We embraced. We talked. We laughed. I surprised her with my honest tears. She astonished me with her life of forgiveness.

Back in the states one month later, I found myself kneeling on the floor again.

I was wrestling down a feeling that not all was as it seemed. I was witness to what suffering and pain can midwife in a heart that is willing– real love. But in this privileged light, my Christian narrative felt suspicious, and more than a little suspect. This made me wildly uncomfortable and I found myself completing Olympic-style mental gymnastics to reason the darkness away.

I spoke out loud an astonishingly disruptive prayer.

“God, something’s not right. What I was satisfied with in my life just isn’t enough any more. I am frustrated. I am confused. I worry about Esperance, but this is just too big–her suffering is multiplied by millions of women in hundreds of places in thousands of violent ways. I thought I could take it God, but I can’t.”

I could not shake the shivers working up my spine every time I thought of the woman named “Hope”. We had seen each other. The fact that our lives were connected haunted me. Grieved, I asked God to remind me of His call and purpose, and the words of an old college chaplain came back to me:

“God…commands us to do something about what we know.”

What did I know? I knew Esperance’s story. And in knowing her story, I knew the stories of millions of women who live in war. The kind of war where the target on your back is a double X chromosome.

What do we know? I believe we know too much now to turn away from our feelings just because it is uncomfortable. “The truth does not change,” blasts writer and modern day prophet Flannery O’Connor, “according to our ability to stomach it”.

May we do something with what we know.

For me, I carry an electronic image of Esperance’s thumbprint with me everywhere I go —it is her signature, the only one she has, courageously stamped underneath three words she insisted be written– “Tell the world.” Esperance knows she is giving her story away, her pain and her redemption. She was not undone by her war-battles, but instead made her mark for the sake of her suffering sisters.

She knows she wants the violence to stop. And now I know so do I.

Today I willingly add my mark to hers. Side by side one becomes two, becomes ten, becomes a thousand—

becomes one million thumbprints.

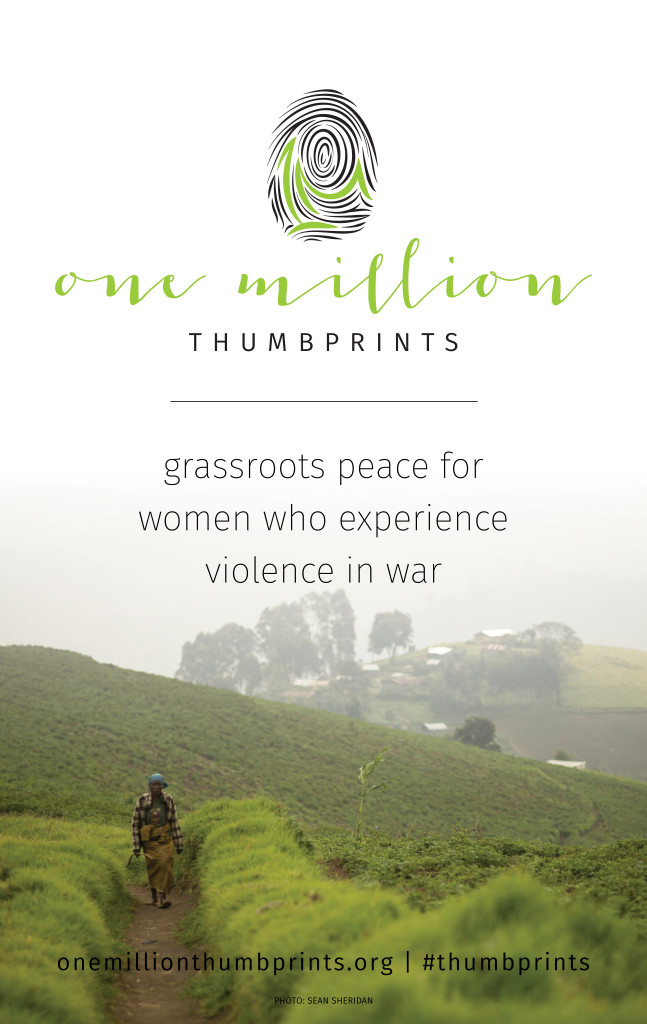

Belinda Bauman is the Founder of One Million Thumbprints, a grassroots campaign seeking to catalyze a groundswell of people focused on overcoming the effects of war against women through storytelling, advocacy, and fundraising.

[…] post, by Belinda Bauman, originally appeared on the Allume blog on September 25, […]